Services/Shoulder | Lemak Health

Anatomy

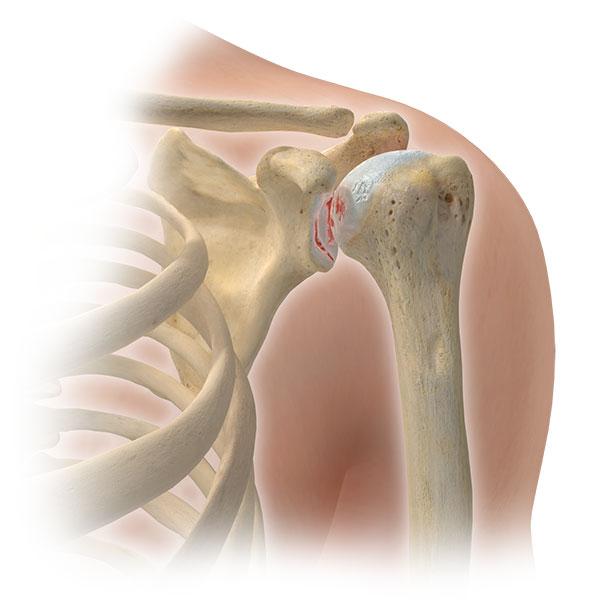

The shoulder joint is made up of 3 bones: the humerus (upper arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle (collarbone). The shoulder is the most dynamic joint in the human body and allows the shoulder a remarkable range-of-motion in many different directions. Movement at the shoulder joint is accomplished through the activation of different muscles, with more than ten muscles in the upper arm that help your shoulder flex, extend, rotate, cross your body, and reach out!

Four of these muscles (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) make up what we call the rotator cuff. In addition to assisting with movement, the rotator cuff muscles also have the important job of helping keep your shoulder stable.

What is a rotator cuff tear?

The muscles of the rotator cuff all have tendons that attach to the head of the humerus, which is the “ball” in the ball and socket shoulder joint. When your doctor tells you that your rotator cuff is torn, he or she is usually describing a detachment of one or more of these tendons from the bone.

Rotator cuff tears are as unique as the people that have them: each one is a little bit different. In some cases, only part of the tendon is torn. These are known as partial tears. Other times there is a complete, or full-thickness, tear, which implies a complete detachment of the tendon from the bone.

What causes rotator cuff tears?

Rotator cuff tears are generally classified as either acute or degenerative.

In acute tears, the tendon is torn from the bone at the time of a specific injury. Types of injuries that can cause acute tears include falling on an outstretched arm, lifting something that is too heavy, and dislocating a shoulder.

Degenerative tears, on the other hand, occur over a long period of time without a specific injury. Unfortunately, tissue degeneration occurs naturally as we age and our bodies gradually become less capable of repairing damaged tissue. There are several factors that can contribute to accelerating tissue degeneration including repetitive stress, poor circulation, and tobacco use.

I have a rotator cuff tear, what are my options?

The recommended treatment for rotator cuff tears is individualized for each patient depending on their age, overall health, functional needs and radiographic findings. For patients with a painful shoulder and evidence of a rotator cuff tear on MRI, treatment options can be broken down to surgical and non-surgical.

Non-surgical Treatment

The goal of non-surgical treatment is to reduce pain and restore function of the shoulder without surgical intervention. With non-surgical treatment the rotator cuff tear does not heal back to bone. Even though the tendon cannot heal without surgery, non-surgical treatment can significantly alleviate pain and improve function to levels where surgery is not necessary. Non-surgical treatment options include:

- Physical Therapy. This is the most important intervention. The shoulder is a complex joint and has many muscles that contribute to its function. In painful shoulders with rotator cuff tears, there are normally weaknesses in other muscle groups that need to be corrected. Improving the function of these muscles and other shoulder mechanics allows less dependence on the torn rotator cuff, which helps to reduce symptoms.

- Rest and Activity modification. Pain and inflammation are intimately associated in a self-perpetuating cycle. Breaking this cycle, and allowing inflammation to resolve with a short period of rest and avoidance of painful activities can help resolve the recurrence of pain or lessen the severity of pain if it returns.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). This group of medications includes Aleve and ibuprofen, as well as other prescription strength medications.

- Shoulder injections. Injection of medicine directly into the shoulder joint can also be considered.

- Corticosteroids are medications that reduce inflammation and are often injected into the shoulder to alleviate pain. There is some evidence that steroid injections may worsen pre-existing tears and worsen the bone quality of the rotator cuff attachment site. In my practice, I try to avoid steroid injections for rotator cuff tears for these reasons.

- Ketorolac is an NSAID that is demonstrating favorable outcomes as compared to steroids for improving pain and minimizing unwanted side effects. This injection is more likely to be considered and offered than a corticosteroid injection in my practice.

Non-operative treatment is successful in about 50% of appropriately selected patients. The best candidates for a good outcome with non-operative treatment for painful rotator cuff tears are patients that have lower functional demands, shorter duration of symptoms, smaller tears, and minimal atrophy of affected muscles.

The major advantage of successful non-operative treatment is the avoidance of surgical risks and the longer recovery time needed for surgical repair. The risks of non-operative treatment include unsuccessful relief of pain, minimal functional improvement, progression of tear size and muscle atrophy, and possible worsening of symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment for rotator cuff tears is recommended for patients that have failed non-operative treatment, and for select patients with tears that would benefit from early intervention. The goal with surgical treatment is to heal the torn tendon back to bone allowing restoration of full strength and function after rehabilitation.

In most cases, rotator cuff repairs are performed using an all-athroscopic technique. This is a minimally invasive technique where the surgeon makes small incisions in the skin that serve as portals to access the shoulder joint. A small camera can then be placed into the shoulder allowing the surgeon to visualize the tear and repair it using specifically designed instruments while causing minimal trauma to surrounding structures. In some cases, when tears are very large or retracted, a larger incision must be made to allow “open” access to the shoulder.

Successful repairs are accomplished by reattaching the torn tendon to bone while creating a new blood supply to deliver the nutrients needed for the tendon to heal. Suture anchors, which are small surgical devices implanted in bone, are used to hold the tendon in place until it heals with the aid of the new blood supply. The new blood supply is created by making small openings in the bone at the site of repair and allows blood products, stem cells, and growth factors to access the repair site and complete the healing process.

Surgery does expose the patient to risks of complications. Some of the more common complications include re-tearing of the tendon, stiffness, infection, blood clots, and medical complications from anesthesia. Diabetes, tobacco use, larger tears, and tears associated with large amounts of muscle atrophy all increase the risk of post-operative complications.

Outcomes of athroscopic rotator cuff repair are good. The techniques and understanding of rotator cuff repair continue to improve at remarkable rates, and recent studies demonstrate satisfactory outcomes in over 90% of surgeries. Surgical repair has success rates upwards of 97% for significant pain relief. Functional outcomes show that 80% of patients with degenerative tears will regain at least 80% of their normal function, or the function they had before their shoulder pain began. With acute injuries, functional outcomes are even better.

Is surgery right for me?

The decision to have surgery is a big one and should be made with your physician. Surgery will or will not be recommended based on the information you provide the physician. It is important to provide as much information as you can about your pain, functional needs, medical conditions and lifestyle to allow your physician to appropriately counsel you.

What can I expect with surgery?

After surgery, you will begin a rehabilitation program outlined by your physician. This program is specifically designed to optimize your outcome and allow you the quickest return to a normal lifestyle. You will need to be able to attend outpatient physical therapy 1-2 times per week for several weeks and be compliant with a home exercise program as directed by your physician and therapist. If you are unable to do the appropriate rehabilitation, you should avoid surgery. Rehabilitation for rotator cuff surgery is never less than 3 months and rarely more than 6 months to return to full activity.

You can expect some pain after surgery. Our intra-operative and post-operative protocols are designed to keep your pain as minimal as possible. You will be prescribed multiple pain medications to take post-operatively to help manage this pain. Most patients will be able to have their pain controlled well enough within two weeks to not require the use of narcotic pain medication.

Your return to work will depend on the demands of your job. If you have a desk job, or one that requires only minimal physical activity, it is not uncommon to only miss a few days of work after surgery. If your job requires manual labor, return to work will be determined by your progression with physical therapy and possible accommodations your employer can make for you to return with activity restrictions.

There are no set rules for when you can start driving with one exception: you are not allowed to drive while taking narcotic pain medication. Many people will be able to start driving within a week. If you do decide that you are ready to drive after surgery, it would be advisable to start in areas of minimal traffic to make sure your reaction time and comfort is sufficient to allow you to drive safely around other cars.

Appointment